This page is dedicated to those who served in the war from Philadelphia and the surrounding area. It is a place for you, the visitor, to share the stories of your family members and friends who served in the military, medical relief services and the numerous charitable and relief organizations which did so much to support the war effort and our service men and women. Please feel free to submit your knowledge and memories so their stories can be shared and remembered.

To submit your stories, please email PhillyWWIYears@gmail.com

John Whiting Friel was a native of Centreville, Maryland but he attended Roman Catholic High School of Philadelphia and graduated in 1910. Following graduation, he attended the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and graduated from there in the class of 1915.

During World War I’s great Battle of the Meuse-Argonne, on Nov. 2, 1918, Corporal Friel and two fellow soldiers, under heavy enemy machine-gun and artillery fire, swam across the Escaut/Scheldt River to complete the construction of a crucial footbridge necessary for the crossing of American troops. The two soldiers with Friel were killed during the action. However even though wounded, Corporal Friel made it to the other side and completed the footbridge enabling the troops to cross.

For his action, Friel was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, the Croix de Guerre with 2 palms from France, the Croix de Guerre from Belgium, and the Purple Heart. During the war Friel also took part in six other major offensives. He left the service with the rank of Captain.

In civilian life Mr. Friel worked for the Standard Press Steel Company for 42 years, retiring as Executive Vice President. In 1963, he was named National Commander of the Legion of Valor, an organization dating back to the Civil War for military personnel who have been awarded the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, or the Navy Cross. In recognition of this honor Mr. Friel was honored by President Lyndon Johnson at the White House.

Throughout his life Mr. Friel remained active in veteran, patriotic and charitable organizations. He was also a noted bibliophile, with his personal library containing a Gutenberg Bible.

John Whiting Friel died at the Union League in Philadelphia on May 27, 1970 at the age of 78. He was survived by his wife Zelia Cowdrey Friel. His legacy was so revered that his obituary was printed in the Philadelphia newspapers and also the New York Times. He is buried in the family plot in St. Peter’s Cemetery in Queenstown, Maryland.

My thanks to Christopher Gibbons for submitting the story of John Whiting Friel.

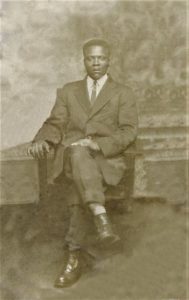

Arthur Henry Showell

ARTHUR HENRY SHOWELL

Arthur Henry Showell (shown in 1920) was born in Philadelphia on June 23, 1894, to Charles and Delia Showell. The Showells had come to Philadelphia from Maryland. Charles and his family lived at 1625 Kater Street. However, the 1910 census shows that the family moved to Selbyville in Sussex County, Delaware.

Between the 1910 census and 1916, Arthur met Beulah L. Purnell. The couple would have a child, Marie, and eventually marry, in nearby Berlin, Maryland. Soon after Marie’s birth Arthur returned with his new family to Philadelphia and lived at 750 S. Clarion Street. Sometime after the Showell’s return to Philadelphia, they had a second child, Hurley. In May 1917, one month after the United States declared war on Germany, Congress authorized a draft for the first time since 1863. On June 5, 1917, just 18 days before his 23rd birthday, Arthur Showell registered for that draft.

On October 27, 1917, Arthur was called to the colors and entered the United States Army. The military, like American society in general, was segregated and Arthur was assigned to the 368th Infantry, Company D of the 92nd Division. The 92nd Division had been organized in 1917 and was composed of African-American soldiers from the forty-eight states. The Division was nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers Division” and the men wore a shoulder sleeve patch with the image of the American buffalo. By June 27, 1918 the Division and Arthur were in France. After additional training, the men were sent to the front. However, they would be stationed alongside French troops because American and British units refused to have black soldiers with them in combat.

Arthur was with the 368th when it faced its “baptism of fire and gas” in the St. Die sector of the Vosges district of France in August of 1918. The St. Die sector formed the southeastern tip of a battle line from the North Sea to the Swiss border. The regiment was ordered to clear the sector of German troops. Just prior to the Division’s arrival, the American 6th Infantry had extended the front by a few miles and captured the town of Frapelle, an important highway and railway route. Arthur’s Division relieved the 6th Infantry and took over the sector. However, the Germans wanted Frapelle back and mounted a counter assault just as the 92nd arrived.

The 368th along with the 365th, 366th and 367th. (other black regiments of the 92nd Division), took the brunt of the German assault. From August 25 to September 20, these regiments were subjected to intensive bombardment including shrapnel bombs, mustard gas and flame projectors. Finally the Germans mounted a full infantry attack to retake Frapelle. This attack was beaten back after a ferocious fight. Intermittent battles and aerial bombardment continued up to the time the Division was relieved.

The 92nd was next transferred to participate in the Meuse-Argonne offensive scheduled to begin on September 25th. The 368th was moved to Binarville. In front of them were miles of barbwire and machine-gun emplacements. Numerous assaults were made against the German positions over the next four days. Binarville was finally taken by the 368th but at a cost of 450 killed, wounded or gassed.

On October 5th the 92nd was ordered to the Marbache sector along the Moselle River. From this sector attacks were made across the Moselle towards the German stronghold of Metz. The 92nd consistently drove the Germans back in battle after battle. The fighting here continued until 10:45am on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918.

Arthur left Europe on February 15, 1919, to return home. He was honorably discharged on March 4, 1919, at Camp Meade, Maryland. On returning to Philadelphia, he lived with his family at 1217 Kimball Street and worked for the A. H. Geuting Company, which manufactured footwear and accessories until his death at the age of 49 on June 30, 1943.

Arthur’s relatively early death at 49 years old may have partially been from his exposure to gas in battle. There is also the possibility that while in Europe he was exposed to the Spanish Influenza. Either exposure would have weakened his system. It should also be noted that Arthur’s willingness to serve his country continued even after his experience in the Great War. Although he was past the age limit, four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor in April 1942, Arthur Henry Showell again registered for the draft.

My sincere thanks to Brice Showell for sharing with me the story of his great-uncle Arthur Showell.

Elmer Albert McAuley

Elmer Albert McAuley was born April 22, 1894, in Philadelphia. His father, James McAuley, was a weaver who immigrated to America from Ireland in the early 1870s. His mother, Mary Murdock McAuley, was the daughter of Irish immigrants. Elmer was born into a large family with eight older siblings.

On July 2, 1917, Elmer was living with his widowed mother at 2029 E. Sergeant St. and was a plush-maker at the Baxter, Kelly & Faust Inc. mill at C and Tioga streets. Later in 1917,

he joined Company F, 313th Infantry Regiment, at Camp Meade, Md. Despite the 313th’s nickname of “Baltimore’s Own,” the unit had many Philadelphia men in its ranks. In July 1918, the 313th Infantry sailed for France as part of the American Expeditionary Forces’ 79th Division. He survived the 313th’s mauling during the battle of Mountfaucon, France, on the first day of the AEF’s Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

According to the 79th Division Association History Committee’s book “History of the Seventy-ninth division, A. E. F. during the world war: 1917-1919,” Pfc. Elmer A. McAuley was killed on Oct. 12, 1918, while the 313th occupied trenches in Troyon, Lorraine, France, overlooking the river Meuse. The book also states that the 313th’s casualties from October 8 to October 27 were almost all caused by German shellfire. Strangely, a later funeral announcement and headstone have his date of death as Oct. 23, 1918.

Although the book confidently names his date of death, the Dec. 2, 1918 edition of The Washington Post lists Elmer as missing in action. His body was apparently recovered and buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery near Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France (shown below). His final resting place was discovered there by his brother, U.S. Navy Petty Officer John Murdock McAuley, who made preparations to have his body exhumed and returned to Philadelphia for reinterment.

On Sept. 3, 1921, nearly three years after his death, a funeral was held at Elmer’s mother’s house on East Sergeant Street, and was attended by members of the 313th Infantry, Kensington Post 68 of the American Legion, and Lincoln Circle No. 8 of the Brotherhood of America (shown here).

He was buried in his parents’ burial plot at North Cedar Hill Cemetery. (shown here).

My sincere thanks to Matthew Richards for sharing this story of his great-great grandmother’s brother and keeping his memory and heroism alive.

William Leopold was born in Germany in 1897 and came to the United States with his family at the age of 4 in 1901. The family came through the Immigration Station at Delaware and Washington Avenue. After living in Camden, New Jersey for a few years the family moved to Philadelphia and lived in Roxborough on East Shawmont Avenue.

William Leopold was born in Germany in 1897 and came to the United States with his family at the age of 4 in 1901. The family came through the Immigration Station at Delaware and Washington Avenue. After living in Camden, New Jersey for a few years the family moved to Philadelphia and lived in Roxborough on East Shawmont Avenue.

After the United States entered the war, William enlisted in the Pennsylvania National Guard (which would become the 28th Division) in September 1917. His mother was concerned that if he went to war he might be fighting against one of his German relatives. But William believed he had to do his duty for his adopted Country.

William served in France as a machine gunner from May 1918 to April 1919. He also kept a diary of his time abroad which presents a vivid picture of a soldier’s life combining boredom, excitement, uncertainty and bad or insufficient food. He saw intense fighting around the town of Fismes, France near the city of Reims from August 8 to August 12. On August 30th William was gassed. He was sent to a hospital in Nantes for care and to recuperate. While there the accompanying photograph was taken. While on his way back to his unit the Armistice was declared. He spent the next several months training and waiting to return home.

After coming home William spent time at Markleton Hospital in Western Pennsylvania for additional treatment from the effects of the gas. After leaving there he resumed his trade as a cabinet maker with Frederick W. Hosback at 2415 South Street, Philadelphia. He worked there until 1939. He then worked for F.Weber and Sons, an art supply company, at 1224 Buttonwood Street. He remained with Weber and Sons for the rest of his life.

William married Bertha Frances Kern after the war and lived at 4111 Manayunk Avenue with his parents until 1937 when William’s family moved to 4232 Mayayunk Avenue where he lived until he died in 1957 at the age of 60. William had two children, Gretta and Eric. In 2014, William’s daughter Gretta and her husband traveled to Fismes to see the bridge over the Vesle River that had been the object of the fighting her father had taken part in. In 1927 the State of Pennsylvania rebuilt the bridge as a memorial to the men of the 28th Division. She found the people of Fismes very welcoming and grateful for the sacrifice made by her father and the men of the 28th even after all these years.

James Martin Fenner, Jr. was from 1346 South Lindenwood Street in Southwest Philadelphia. On June 6, 1916, at the age of 19, he enlisted in the Pennsylvania National Guard. He was assigned to Company A, 2nd Infantry, 28th Division. Later in June his unit was federalized for service at the Mexican border. He was promoted to Corporal and assigned to Battery A, 2nd Field Artillery. He was later promoted to Sergeant, Battery A, 108th Field Artillery in command of the second section. This unit was called the “Black Jack Gun Crew” and its howitzer nicknamed “Bouncing Betty”.

Upon America’s entry into the war the unit was called into service on July 15, 1917. They went for training to Camp Hancock near Augusta, Georgia and eventually sailed for Europe on May 19, 1918. They arrived in La Harve, France on June 5, 1918. Once there they received additional training at Camp de Mexcon, Vannes, France on the 155mm Schneider howitzer, model 1917.

Battery A fired its first shot on August 18, 1918 at Courville, on the Oise-Aisne sector. During its service Battery A held numerous positions in France and Belgium. Finally, it was located at Nieuwenhove, Belgium from October 30th till the Armistice.

Sergeant Fenner was recommended for exceptional meritorious service on October 30, 1918. The Order reads “On the night of September 8, 1918 Sgt James M. Fenner 1251501, Battery A, 108th Field Artillery, displayed unusual coolness, leadership and devotion to duty and by his example kept his cannoneers at their post, thus maintaining the fire of his gun when the battery position north of La Bonne Maison, near Courville, France, was subjected to enemy shellfire.”

Sergeant Fenner’s battle record includes: Fismes-Vesle Sector, August 15, 1918-August 18, 1918; Oisne-Aisen Offensive, August 18, 1918-September 10, 1918; Meuse-Argonne Offensive, September 26, 1918-October 10, 1918; and Ypres-Lys Offensive, October 30, 1918-November 11, 1918. He returned home to Philadelphia on May 16, 1919 and went to work for Wanamaker’s. In 1928 he married and the couple moved to Teaneck, New Jersey. James Fenner died on January 27, 1983.

Augustus (Gus) Herman Else was born in Butler, Pennsylvania in 1891. He later moved to Philadelphia and resided in the Logan area of the city when he joined the army. He served as a private in Battery E, 80th Field Artillery. He was honorably discharged on June 26, 1919. According to the census of 1920 he worked as a carpenter at the Potter Oil Cloth Company. He died on January 24, 1941 and is buried in Philadelphia National Cemetery at Haines Street and Limekiln Pike.

On March 19, 1917 the Navy became the first branch of the U.S. Armed Forces to allow women to enlist in a non-nursing capacity. On March 21, 1917, Miss Loretta Perfectus Walsh, 21 years of age and living at 734 Pine Street was the first woman to enlist in the United States Navy under this new rule. She took the oath of allegiance as a chief yeoman.

On March 19, 1917 the Navy became the first branch of the U.S. Armed Forces to allow women to enlist in a non-nursing capacity. On March 21, 1917, Miss Loretta Perfectus Walsh, 21 years of age and living at 734 Pine Street was the first woman to enlist in the United States Navy under this new rule. She took the oath of allegiance as a chief yeoman.

Miss Walsh was the first of 2,000 Philadelphia women who joined the military during the war. These Female Yeomen, also known as ‘yeomanettes’, performed duties which ranged from clerical work and recruiting to production jobs in ammunition factories as well as design work, drafting, translation, and radio operating responsibilities. When the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, there were over 12,000 yeomanettes in the Navy and 300 ‘marinettes’ in the Marine Corps. Women serving as yeoman received the same pay and benefits as men. Something unheard of at the time. Loretta Walsh died at the age of 29 on August 6, 1925 after contracting tuberculosis. She is buried in Olyphant, Pennsylvania.

Philadelphia men were well represented in the Navy. This is a photograph of one Philadelphian, Patrick Gallagher, during his service. As a young man, Gallagher immigrated from Glenties, County Donegal, Ireland. Following the war and in appreciation for his service he was granted American citizenship. After the war Mr. Gallagher started a construction company and lived in Philadelphia until his death. (Courtesy of Collins/Gallagher family archives.)

Service by Philadelphians both before and after America entered the war crossed all social and economic lines. The children and grandchildren of some of the oldest, wealthiest and most prominent Philadelphia families “did their bit” alongside the children of recent immigrants. One such young man was Julian Cornell Biddle. Biddle was born in 1890 into one of the richest and most respected families of Philadelphia. He graduated from Yale in 1912 and worked for a time as secretary to the United States Minister to Japan.

When war broke out in 1914 Biddle took up flying, eventually receiving his pilot’s license at Essington. He left the comfort of his home at 1821 DeLancey Street for France in 1916 and joined the Lafayette Flying Corps. Biddle saw action in numerous dog fights. But on August 8, 1917 his plane went down into the North Sea. His body washed ashore some days later showing signs of bullet wounds suggesting his death was the result of combat. In January 1918, Biddle was awarded the Aero Club of America medal for valor and distinguished services. He was also awarded the Lafayette Flying Corps Ribbon by the French Ministry of War.

Dr. Vincent “Vincenzo” Diodati was a graduate of Roman Catholic High School, class of 1906 and a graduate of Thomas Jefferson Medical College. Dr. Diodati practiced medicine at 1222 South 12th Street, and at Howard Hospital, The Southeast Dispensary and The Italian Hospital. He was also the medical consultant for many Italian fraternal organizations. He enlisted in the army on the day American declared war and was commissioned 1st Lieutenant. He sailed for Europe on August 2, 1917 and was attached to British forces. He was placed in command of the 35th Royal Army Medical Corps and was the first American to be given such a position.

Dr. Vincent “Vincenzo” Diodati was a graduate of Roman Catholic High School, class of 1906 and a graduate of Thomas Jefferson Medical College. Dr. Diodati practiced medicine at 1222 South 12th Street, and at Howard Hospital, The Southeast Dispensary and The Italian Hospital. He was also the medical consultant for many Italian fraternal organizations. He enlisted in the army on the day American declared war and was commissioned 1st Lieutenant. He sailed for Europe on August 2, 1917 and was attached to British forces. He was placed in command of the 35th Royal Army Medical Corps and was the first American to be given such a position.

He went to France in August, 1917. While there, Dr. Diodati was constantly under fire. He was gassed twice and wounded 3 other times. He served at Locon, Pacut Wood and Via Chappelle. He was gassed at Annequin but remained at his post. He was wounded at Lillers in the Bethune sector and gassed again and wounded by shrapnel at Marquain. On March 16, 1919 he was awarded the British Military Cross for his bravery and gallantry. The award was presented to him personally by King George of Great Britain.

Edward J. Donahue, Sergeant, was at age 53, one of the oldest volunteers for the U.S. Army. Army regulations prohibited accepting anyone into the service over 41 years of age. Donahue, of the 5200 block of Chestnut Street worked as a horseshoer in civilian life. He said that he believed he was accepted into the army because he kept his hat on, covering his bald head. Donahue served in France during the war.