January 4, 2016

THE 1916 MUMMERS PARADE

The New Year arrived with partly cloudy skies and the chance of rain and snow. The high would reach 40° with the evening low near 26°. 1916 is a Leap Year and Philadelphia welcomed it like no other place on earth. The Mummers were out in force as 12,000 merry makers marched North on Broad Street. The parade, which began at Broad & Porter Streets, turned the thoroughfare into an immense stage where the goings on in the world were shown, mocked and in some cases admired. It all started at 8:30am and was still going on late into the evening in various sections of the city. The official parade ended at Girard Avenue.

Untold thousands packed the sidewalks all along the parade route and watched the marchers deal with every pressing question of the day including war, industry, prohibition and women’s suffrage. They did so candidly, humorously and sometimes a bit scandalously. In dealing with the war, battles were fought between Italians and Germans but in these fights the Italians bombed with spaghetti and meatballs while the Germans answered with cheese and onions. There were German and Austrian Dukes with Turkish pashas cavorting with English, Russian and French generals. And Indians danced with cowboys as Mexican bandits and chorus girls cavorted. And of course there were clowns of every shape, color and type.

It was the color that makes this parade a truly splendid spectacle. Every color of the rainbow was employed on satin and silk which sparkled even under an overcast sky. The Comic Clubs led the merriment. They included: J.J. Hines, The White Caps, Harry Wall, Wheeler, Owl, The Sauer Kraut Band, Marching Social, William Woodward, Kensington Outing Club, Blue Ribbon, George A. Persch, Sweet Lemon, Dark Lantern, Zuzu, D.R. Oswald, M.A. Bruder, Ranch 102, Lenni Lenape, Early Risers, Dickey, Big Beer, Court Fairmount, Jack Rose Accordion Band, The Meadow Larks, Clearfield, Pickaninny, Royal Italian Crown, Jovial, Cartoonists Reunion, Alva, The Six-Thirty and Broadway Sons of Rest.

The White Caps had over 600 men in line some dressed as Charlie Chaplins, Uncle Sams, butlers, negros and tramps. One of their more humorous groups marched as “White House Cupids” claiming credit for our President’s recent nuptials (shown below).

The Sauerkraut Band of Pottstown were dressed in red and green and serenaded with many traditional songs. The Jack Rose Accordion Band paraded as an army made up of Irish, German and Yiddish soldiers.

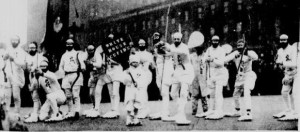

The Fancy Clubs were next and included Silver Crown, Passyunk Ranch, Charles Klein, Federal, Bobby Morrow, Lobster Club, Cumberland Valley from Chambersburg, Pennsylvania and The Hikers of 1898. Silver Crown, the oldest club in the city, was led by its captain Michael Quigley and made a spectacular appearance with his cape carried by almost 100 page boys (shown below).

Lobster Club followed and was led by a bevy of female impersonators including B. White and Frank Carter (shown below on right). Carter, who is a many time champion impersonator, wore a black & white clingy creation topped with a beautiful headdress. Many of the other “Ladies” wore décolleté gowns revealing scandalously bare shoulders. The Charles Klein Club produced gorgeous king clowns, groups of Japanese dancers and a group depicting Ireland’s ambition for their own king.

The string bands were the last division in the parade. They were led by the Victoria String Band and followed by Talbot, Trilby, Fralinger, Ford, Eureka and Kaufmann . One of the more delightful sights was that of 4 year old John Fralinger, Jr. leading the Fralinger String Band with joyous abandonment. By the time Talbot rounded City Hall a light snow began to fall. This was later followed by rain but even that could not dampen the enthusiasm of the marchers or the joy and wonderment of the spectators.

And as for the prizes awarded this year, there was a generous fund authorized by city councils. In the Fancy Division, Lobster New Year Association took 1st prize and received $650.00. Charles Klein finished 2nd and received $400.00. Third place went to Silver Crown New Year Association along with a purse of $200.00 and Bobby Morrow New Year Association finished 4th and received $150.00. In the Comic Division the White Caps were awarded the 1st prize of $650.00, M.A. Bruder New Year Association finished 2nd and received $350.00. Third Place went to the ZuZu New Year Association with a prize of $200.00. D.R. Oswald New Year Association was 4th and won $150.00. Harry Wall New Year Association was 5th winning $75.00 and the Sauer Kraut Band of Pottsville, Pa. placed 6th taking $60.00. Among the String Bands, Talbot took 1st prize followed by Victoria and then Fralinger in 3rd place.

In all it was a wonderful way for the city and its people to welcome 1916.

January 8, 2015

BRINGING IN THE NEW YEAR PHILADELPHIA STYLE:

THE 1915 MUMMERS PARADE

January 1, 1915 came in with bright, sunny and clear skies, but there definitely was a chill in the air. The high temperature that day only reached 34°, while the low at night dropped to 13°. The official parade on Broad Street stretched for five miles, from Broad and Porter to Broad and Girard. It began precisely at 8:00am with a platoon of mounted police leading the march. They were followed by Councilman John Baizley, mounted on his own spirited steed, who was given a place of honor because he had obtained an increase in the appropriation for the shooters that year.

The first mummer to cross the starting line that year was Captain Michael Quigley who led the Silver Crown Association. Captain Quigley’s cape (shown below) was studded with thousands of roses and stones. The cape filled almost the entire width of Broad Street and was carried by over 40 page boys.

Twenty-four clubs and 12,000 shooters followed Silver Crown, each a dazzling array of color and size. The Trilby String Band provided an interesting musical contrast dressed as Turks and playing romantic music. It also broke into the favorite tune of the day “Tipperary” which thrilled the crowds. Other bands also entertained. There was the Kucker String Band, the Oakley String Band, the Oswald String Band, the Jacot String Band, Pat Casey’s Jewish Band, the Sauerkraut Band of Pottsville and the Fralinger String Band led by Joseph Ferko, who was perhaps the most handsome band captain dressed in a pink cutaway jacket with a purple satin top hat and cane.

The parade was like a glittering procession, an ever-changing rainbow of color dancing to lively music. The pageant told the story of the city and the world of 1914 with dancing clowns, extravagant Indians, kings and princes and garishly arrayed “belles.” Many of the costumes cost several hundred dollars to produce and some as much as $3,000.00. Of course the war in Europe was addressed with portable forts, armored automobiles, areoplanes, zeppelins and battleships on land.

Crowds packed the sidewalks and in many places were 10 deep. Every window in every home along the route was filled with spectators. Even at City Hall the crowd formed early, knowing it would be at least 2 hours before they would see the first Mummer.

At City Hall there was a reviewing stand for members of the city councils. Another reviewing stand held the Mayor and the judges of the clubs in the parade: Thomas J. Walker of the Philadelphia Public Ledger, Charles P. Garde, editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer and Joseph Kelly. Motion-picture camera operators and photographers were perched on sheds reached by ladders. One ladder was stolen during the parade, leaving a photographer stranded for a while until policemen were called to get him down.

Only one mishap occurred among the marchers, when the captain of the Lobster New Year’s Club, Joseph Chambers, collapsed just before reaching City Hall. Mr. Chambers was unable to carry the immense weight of his cape and costume any longer. Although he had 75 page boys assisting him, the cape, weighing over 1,000 pounds and extending from one side of the street to the other, was too much for him to bear any longer. Mr. Chambers was helped to his feet by several policemen and a few bystanders. After composing himself for a few minutes, he continued on his trek to the judges’ area where, despite his fall, he would win Best Dressed Captain. A complete list of the prize winners is set out below.

Once the parade on Broad Street reached its conclusion, the Mummers dispersed to other parades and festivities. Some would continue north to march on Columbia Avenue at the invitation of the Columbia Avenue Businessmen Association. Some would march along Girard Avenue in a parade organized by the East and West Girard Avenue Businessmen Association. A few would head to Brewerytown for that neighborhood’s New Year’s Day parade. Others would return to South Philadelphia and parade on Wolf Street between Broad and 10th Streets as guests of the residents. Many if not most would travel down to 2nd Street and march from Washington Avenue to Ritner Street in a parade organized by the South 2nd Street Businessmen Association, finishing the day on the street where it all started many years before.

The Prize Winners of the 1915 Mummers Parade:

Fancy Clubs

1st Prize: Lobster Club – $650.00

2nd Prize Charles Klein – $400.00

3rd Prize Silver Crown – $200.00

Best Dressed Captain – Joseph Chambers, Lobster Club – $100.00

Handsomest Costume – Michael Quigley, Silver Crown – $100.00

Comic Clubs

1st Prize: White Caps – $650.00

2nd Prize: M.A. Bruder – $300.00

3rd Prize: Federal – $200.00

4th Prize: D.R. Oswald – $150.00

5th Prize: Robert E. Morrow – $75.00

6th Prize: D. Campbell – $60.00

Most Comic Dressed Captain: Fred Allgerier, White Caps – $100.00

Most Comical Costume: W. J. Rementer, Captain, Bruder Club – $50.00

Floats

1st Prize: “Yellow Convict Ship”, White Caps – $150.00

2nd Prize: “Made in Philadelphia”, M.A. Bruder Club – $100.00

3rd Prize: “Eva Fay, Mind Reader”, Federal Club – $75.00

4th Prize: “Irish Queen”. M.A. Bruder Club – $50.00

5th Prize: “Italian Hotel”, Federal Club – $35.00

Brigades

1st Prize: Sauer Kraut Band of Pottsville – $100.00

2nd Prize: Trilby String Band – $60.00

3rd Prize: “Federal League Jumpers”, M.A. Bruder Club – $50.00

4th Prize: “Irish Sharpshooters”, White Caps – $25.00

Special Features

1st Prize: Oakley String Band – $100.00

2nd Prize: Frank Carter (Female Impersonator) Lobster Club – $50.00

3rd Prize: “Kaffir Chief”, J. Wesley Meyers of John Borrelli Club – $25.00

December 18, 2014

A LITTLE HISTORY OF THE PHILADELPHIA MUMMERS PARADE

For those of you that march in the annual Mummers Parade on New Year’s Day in Philadelphia or are just interested in a little bit of the history of the celebration and spectacle of this wonderful tradition, I thought you might find this 1914 article of interest.

THIS ARTICLE IS REPRODUCED FROM THE PHILADELPHIA EVENING PUBLIC LEDGER OF DECEMBER 18, 1914

“MUMMERS” OF 50 YEARS AGO

Origin of Philadelphia’s New Year Pageant and Its Growth to Its Present Popularity

The New Year shooters are sometimes referred to as “mummers” but though that designation originally was the correct one, it is not properly applicable to the clubs which we see in fantastic parade on Broad street on the first day of the year. The mummer is English, while the New Year shooter is the product of our own “Neck.”

The antiquity of the Christmas mummer is admitted, but the New Year shooter does not appear to date back much farther than 75 years, and, as we have known him of late, not more than 50 years. There is, however, a historical connection.

The custom in the “Neck” in the old days was known locally as “Bell Snicklin’.” The quaintly attired youths who visited the old homesteads in the lower part of the city on New Year’s Eve carried bells in their hands or wore bells attached to their costumes. They also carried pistols or guns and fired them occasionally; hence the term, “New Year Shooter.”

All this was before the organization of the New Year Clubs, now so numerous. The old-time shooters in the “Neck” used to travel in small parties and usually were known at all the houses they visited, but instead of attiring themselves as Father Christmas, Beelzebub, The Doctor and St. George, the principal characters in the play of St. George, which the English mummers used to recite on their visits, they had no play. With them went two fiddlers and a man with a triangle or an accordion. One of the company, who may be said to have been the leader, would recite a long piece of doggerel to this effect:

“Mr. and Mrs. ——-

We wish you Merry Christmas and Happy New Year;

We come tonight your hearts for to cheer.

We’ve traveled the neighborhood round and round,

And very good neighbors we have found.

We’ve shot off our guns for a New Year,

And hope that this your hearts will cheer.”

It may be interesting to know that the appealing verses ended with an exhortation to “virtue, liberty and independence,” which sentiment of the Bell Snicklin’ visit was borrowed from the State motto.

Something to eat and drink always followed, and afterward there was a dance to the music of the fiddled and triangle. These occasions used to be looked forward to with delight by all the participants, both visitors and visited. And for a long time the custom was so completely confined to the Neck that it was unknown in the northern parts of the city.

What is regarded as the first real organization of New Year shooters was known as the Chain Gang, which is believed to have been formed in 1840. About the time of the Civil War there was a club composed of members or adherents of the Shiffler Hose Company, and known as Santa Anna’s Cavalry, which made a tour of the southern part of the city on New Year’s Eve and the following day. After the Civil War such clubs as the Golden Crown, the Silver Crown and the Clements New Year Association sprang up, and early in the 70s the clubs ventured as far north as Market street. The Shooters paraded on the sidewalks, for the streets were muddy and badly paved with cobbles. The clubs became numerous, and from the Neck finally spread to all parts of the city. Within recent years similar organizations have appeared in other cities.

So much money was spent upon the displays here as to cause a demand that the clubs should join forces and parade on Broad street. About 16 years ago, after long negotiation intended to minimize the rivalry, an agreement was reached, and the annual pageant was instituted. The city appropriates considerable money in prizes. Some of the clubs spend a great deal for their costumes, although few own them. A captain’s suit used in one of the parades is said to have cost $6000, the costumer receiving $2000…. [The remainder of the last sentence of the article is unreadable]

September 1, 2014

The British World War I Memorial in Philadelphia

It may seem a bit curious that a memorial to British soldiers, sailors and marines who served in the First World War is located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Cross of Sacrifice that stands in Northwood Cemetery, however, is both a monument to those Britons who served their country in The Great War and a testament to the deep ties which exist between Great Britain and America, especially with the people of Philadelphia.

The story behind the memorial begins in 1922 when the then British Consul in Philadelphia, Gerald Campbell, was transferred to San Francisco. Mr. Campbell’s friends and admirers wanted to provide him with a gift in appreciation for the service he had performed for the British citizens of the area and for the work he had done in cementing the relationship between Great Britain and the people of Philadelphia. Campbell wanted nothing for himself, but he did request that a plot of land be procured in a local cemetery as a last resting place for British citizens who had made Philadelphia their home. The land was found in Northwood Cemetery in the West Oak Lane section of the city.

Soon thereafter, the members of the British Officers Club of Philadelphia began planning a memorial for Britons who had served in the war and had died in Philadelphia. Prior to the war, an estimated 10,000 British citizens lived in Philadelphia. When the war began, many answered the call to service. Estimates are that about 60,000 Britons left America to fight for the mother country, with over 4,000 of those coming from Philadelphia. Some gave their lives on fields far away. The memorial was to serve as a monument to those lost and also to those who did return to Philadelphia and had since passed away.

The memorial was to be in the form of the Cross of Sacrifice. This monument was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield for the Imperial War Graves Commission and is found in all British military cemeteries throughout the world. It is a freestanding Latin cross on an octagonal base with a bronze broadsword on its face. The Cross in Philadelphia was made of Portland stone cut in England and specially shipped to the United States. It was the first Cross of Sacrifice to be erected in the United States in memory of British servicemen [1].

The dedication took place on a warm, sunny Saturday on June 1, 1929. It began with a parade through the surrounding neighborhood, led by Mr. John Pegg of the British War Veterans of America and followed by American, French and Italian veterans. There were also American sailors and marines from the Philadelphia Navy Yard led by Admiral J. L. Latimer, Commandant of the Navy Yard, and a detachment of the Pennsylvania National Guard, led by Major General William G. Price, Jr. American Navy and Army bands also marched as did the Caledonian Bagpipe Band in their highlander’s kilts.

The location of the monument is on a grassy slope of the cemetery, which gave the ceremony the effect of being in an amphitheater. The British delegation was led by the Ambassador of the United Kingdom to the United States, Esme Howard, and the British General Consul in Philadelphia, Frederick Watson, along with British Army and Naval Attaches to the Embassy.

Along with the American military delegations, the City of Philadelphia was represented by Mayor Harry Mackey and members of the city government. Also in attendance were the members of the other Consular offices in the city, the veteran groups mentioned above and a large crowd of invited guests along with residents from the surrounding neighborhood.

The crowd heard speeches from the assembled dignitaries, beginning with General Consul Watson who said, “I venture to express a hope that this hallowed spot will be henceforward doubly dear to all Britons, as it will serve to remind them of the homeland, while, as they gaze on the Cross of Sacrifice they will remember that Briton and American alike shared in that sacrifice and thank God for this solid rock on which Anglo-American friendship is securely founded.” Ambassador Howard stated “This Cross will therefore be not only a perpetual reminder of the supreme sacrifice nobly made by many, but also a bond of union between the living and the dead on both sides of the ocean.” Major R. Tait McKenzie, President of the British Officers Club of Philadelphia, also spoke and told the crowd that the Cross would stand guard over the graves of those lying under it in “this little triangular spot which will be forever England.”

At the conclusion of the remarks Ambassador Howard unveiled the twenty-two foot tall cross as a trumpeter sounded The Last Post. The inscription on the base of the monument reads:

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND TO THE MEMORY OF THOSE BRITONS WHO SERVED THEIR KING AND COUNTRY AND NOW REST HERE. LET THOSE WHO COME AFTER SEE TO IT THAT THEIR NAMES BE NOT FORGOTTEN

The ceremony concluded with the United States Navy Band’s playing of the Star Spangled Banner and God Save the King.

Ambassador Howard unveiling the monument

The Cross of Sacrifice still guards that “little triangular spot” in Philadelphia. In fact, 57 years after the ceremony of 1929, another burial took place under the Cross with full British military honors. In 1985 the body of a British soldier was uncovered during construction close to the site of the Battle of Germantown which occurred on October 4, 1777. The soldier was probably buried by his comrades close to where he died that day. He was a man of stocky build between 30 and 40 years of age and with a touch of arthritis. By the buttons on his coat, it was learned he was a member of the 52nd Regiment which was then a part of the Scottish Light Infantry Battalion.

On November 2, 1986, the coffin containing this soldier, draped in the Grand Union Flag and carried by members of the Royal British Legion, was taken to the grave site accompanied by British and American veterans and led by Colonel Anthony E. Berry, a representative of the British Defense Ministry. As the coffin was lowered into the ground, the Scottish Pipe Band played Going Home.

When this British soldier lost his life on that October day long ago he was buried by his fellow soldiers in what was then still part of Great Britain. Because of the work of British and American citizens culminating in the dedication of the Cross of Sacrifice, 209 years later this unknown soldier once again rests in British ground.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

[1] A Cross of Sacrifice was previously dedicated at Arlington National Cemetery on November 11, 1927. However, that Cross was dedicated to Americans who had lost their lives while serving with the Canadian and British military.

July 15, 2014

Some Advice For The Ladies Of 1914

I thought I would write something a bit different. In doing my research I have often come across pamphlets, newspaper articles and books aimed specifically at women. I’ve found these works absolutely fascinating in that the picture they present of the lives and roles of women in society then are so much different from today. Granted, these writings were directed toward middle and upper middle class women. But the general picture they painted as to what was proper and acceptable for all women is instructive. Much like the sit-coms and dramas of American television in the 1950s and early 1960s presented an ideal and unattainable view of the American family then, these articles and pamphlets, I believe, did the same for families of the early years of the 1900s.

So, I thought I would summarize some of the information and advice given to women back then and present a little article using those ideas for this entry. On a personal note let me assure you (and especially the women in my life) that the article below does not represent my personal beliefs on how the modern woman should live her life. I present it only as a bit of information and hopefully amusement.

“Remember ladies the peace and tranquility of your home rests on your shoulders. Women must provide a clean, happy and welcoming home. And it is you that must ensure that your husband and children receive healthy, tasty and nourishing meals. With that in mind, provided here is a suggested menu for today.

For Breakfast, chilled raspberries, an omelette, fresh baked rolls and coffee. For dinner, cream of pea soup, stuffed lamb in brown sauce, boiled rice, cake and coffee. For supper, cabbage salad, tongue and cold refreshing lemonade.

And ladies do remember to keep up your appearance for the sake of your family and yourself. Do not present a disheveled or unkempt appearance. Remember cleanliness is next to Godliness. Dress in clean clothes, preferably ones with bright colors and pleasant patterns. And ladies, never use indecent, vexatious or naughty words. A women’s greatest gift is her dignity. And nothing does more to lessen her dignity that the use of crude language. By doing these things you provide an excellent example to your children and provide them with a model to emulate.

And remember ladies, your husband must go out every day to face the trials and tribulations of the work world. When he returns to his home ensure that he is entering a place of peace and tranquility. He will have worked a long, hard day for the benefit of you and your family. Make sure that when he returns home he finds you looking your best, his abode is clean and tidy and a hearty, healthy and delicious meal is awaiting him.”

[Ah, the good old days]

June 29, 2014

Sarajevo and Philadelphia – A Tale of Two Cities on June 28, 1914

On Sunday morning, June 28, 1914 at about 10:45am in the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg were murdered by a young Serbian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip. Others are much more capable and qualified to write of that day in Sarajevo and its aftermath. So I thought I’d write a bit about how the events in Bosnia were viewed in my city that day, Philadelphia.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is 4,557 miles from Sarajevo and has a 6 hour time difference. When the shots rang out in Sarajevo most Philadelphians were still asleep. And they did not read about it in the Sunday morning papers later that day. Because most papers in Philadelphia did not publish on Sunday in observance of the Sabbath. One did, the Philadelphia Inquirer. But the news of the murders hadn’t reached the Inquirer’s offices in time for inclusion in its Sunday edition.

So it was not until Monday, June 29th that Philadelphians learned of the deaths. That is not to say that most Philadelphians knew where Sarajevo was, knew where Bosnia was or knew who Franz Ferdinand was and whether or not he was married to a women named Sophie. Philadelphians like most Americans knew the royal family of Great Britain and who the Kaiser of Germany was but that was because they were in the news much more often than other European nobility. The average Philadelphian just did not pay attention to or care about European royalty.

On June 29th the murders of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie were the headlines on the front pages of the city’s eight newspapers. There were stories recounting the lives of the couple, their morganatic marriage, the reason for the trip to Sarajevo and an account of the assassinations. But the story by no means overwhelmed the news of the day for Philadelphia.

The story shared the front page with the announcement of the death of Anna Brumbaugh, the wife of the Superintendent of Schools of the city, Martin Brumbaugh. She was 53 at the time of her death and had suffered from a long illness. He husband was well known in the city and would become Governor of Pennsylvania in 1915. They also read of the deaths of average citizens like Frank Krause a 21 year old, electrocuted at his job in an ice cream factory on the day after he married the love of his life, 19 year old Julia Solenski. And 39 year old Charles Arndt, who died of a heart attack at one of the city’s public pools while out having a swim on that warm sunny day.

When it came to international news Philadelphians were much more concerned with events closer to home. The ongoing civil war in Mexico was always on the front pages. And the negotiations in Niagara Falls, Canada which arose from the Tampico incident and America’s occupation of Vera Cruz were much more important to the average resident than the killing of an heir to a throne in central Europe. Now also there was trouble in the Dominican Republic at Puerta Plata. On June 29th the U.S.S. South Carolina had fired on Dominican government forces to stop their bombardment of the city and protect Americans living there. Philadelphia, home to a large Navy Yard and thousands of sailors and marines, cared about that.

But Philadelphians were also preparing for 4th of July celebrations. Something they looked forward to in their city perhaps like no other. Some people were planning getaways to the New Jersey seashore and the railroad lines were running specials for one day round trip excursions. And city residents then as now loved their sports. The newspapers covered the daily games of the Athletics and Phillies in professional baseball, the various area cricket clubs, horse racing, boxing and soccer. And a grand regatta was planned on the Schuylkill River for the 4th of July. Teams from Canada, New York City and Detroit were coming to take on Philadelphia’s own Vesper Club, Penn Barge Club, Undine Barge Club and College Boat Club.

Philadelphians did see the events in Sarajevo as a personal human tragedy. They felt sympathy for the children of the Archduke and his wife who were now left behind. And those feelings were expressed by people interviewed by the newspapers. But most people just did not see the deaths as anything affecting their lives. That was true even in the Philadelphia’s Austrian community. Austrians who were interviewed said the assassinations did not concern them. They said Austria was too far away for them to worry about. Many stated that they had come to America to leave this sort of thing behind and that America was their country now.

No one in Philadelphia, America or Europe on June 28th could have possibly known what the assassinations would lead to. Europe still had a few weeks of peace before the shooting started. And America would not be involved for another 2 years and 8 months. Franz Ferdinand and Sophie were the first of 37 million who would go to their deaths. The world was going to change as a result of that day in Sarajevo and one day that change would arrive in Philadelphia.

But on that Sunday, June 28, 1914 Philadelphians went to church, picnicked in one of the city’s many parks or along its rivers, visited with family and friends and perhaps gathered around the Victrola or piano singing songs and enjoying the warm summer day. What happened in Sarajevo would one day affect Philadelphia, just not yet.

May 18, 2014 John Wanamaker: Citizen, Philanthropist, Patriot

John Wanamaker never served in the United States military. He was rejected for health reasons when he tried to enlist in the Union army during the Civil War. But his patriotism and support of the American servicemen was unequaled. This was especially true during the First World War.

Wanamaker was born in in the Grays Ferry section of Philadelphia on July 11, 1838 to Elizabeth Kochersperger Wanamaker and John Nelson Wanamaker, a brickmaker. As a young man he worked in a number of retail sales businesses. He opened his first store in 1861 and after experiencing great success opened his grand department store in 1876 at Juniper and Market Streets in center city Philadelphia just across from City Hall.

When the war in Europe began, Wanamaker joined and supported numerous charitable and relief organizations formed to send food, medicine and clothing to the civilians suffering from the ravages of the conflict. This was particularly true with regard to Belgium. Wanamaker, a devout Christian, was appalled by what he perceived as German barbarity in Belgium. He immediately turned to his friends and acquaintances among Philadelphia’s elite and wealthiest families to mobilize their resources and send help to Belgium.

Wanamaker’s stature in the city ensured his call would not go unheeded. Philadelphia’s merchants, businessmen and old wealthy families answered. Wanamaker chartered the Norwegian ship Thelma on November 7, 1914. The ship was filled with 1,700 tons of food, clothing and medical supplies. It sailed on November 12, 1914. A second ship, the Orn, with an additional 2,000 tons of supplies was sent on November 25th . Wanamaker, who had a great deal of influence in political circles, even petitioned the United States government to offer to buy Belgium for 100 billion dollars in the hopes that the Germans would leave the country. He offered to put up his own fortune to start the campaign to raise the funds.

When America entered the war, Wanamaker redoubled his efforts. He lent his name, time and money to dozens of charitable and relief organization supporting the troops overseas and their families at home. He donated large sums to the five Liberty Loan drives, donated buildings he owned to organizations like the Red Cross, YMCA and The Emergency Aid of Pennsylvania for their work in providing support for the troops and European refugees. He gave his estate in Noble, Pennsylvania for use as an army training ground and camp. He also opened stores in Paris and Tours so American servicemen would have access to clothing and supplies at cost or discounted prices. When Wanamaker was needed he was there.

When the war ended Wanamaker did all he could to help returning servicemen, especially the wounded, find work in his stores. He also offered classes at his store to provide returning men with training to ease them back into the civilian workforce.

John Wanamaker died on December 12, 1922. His legacy is not just the massive, 12 story department store on Market Street. It is his reputation for honor and integrity in his dealings with the public, the treatment of his employees and his work as a philanthropist and patriot. Today an eight foot statute of Wanamaker stands outside Philadelphia’s City Hall looking toward his store. It bears the simple inscription “John Wanamaker, Citizen”.

May 7, 2014 Philadelphia Hospitals, Doctors, Nurses and Staff in The Great War

As the son of a nurse and one whose life was truly saved as a young child by the doctors and nurses of St. Agnes hospital in South Philadelphia, I have always had the greatest respect for those in the medical profession. With that as an impetus I thought I would write something about the role of the medical professionals of this city during the Great War. Philadelphia, like all the major cities of America, sent their doctors and nurses overseas not just to serve with the boys but to heal them, comfort them and when necessary hold their hands as they passed off the mortal coil.

Philadelphia was considered then, as now, one of the premier centers of medical science, education and treatment in America. Beginning with the opening of the nation’s first hospital, The Pennsylvania Hospital by Benjamin Franklin in 1751, the city had a long and notable history as a medical center. It was also a city fortunate to have numerous hospitals, large and small, throughout its environs. And when war came to America these hospitals and their staffs recognized the coming need for trained medical personnel on the front lines.

Even before America’s entry into the war in April 1917, plans were being made at many of these institutions to provide their services should war ensue. Hospital units began being organized to send doctors, nurses and support staff overseas. These hospitals included Pennsylvania Hospital, The University of Pennsylvania Hospital, The Episcopal Hospital of Philadelphia, The Jefferson Medical College, The Presbyterian Hospital of Philadelphia and The Methodist Episcopal Hospital of Philadelphia. Presented below are brief accounts of these Hospital units, where they were stationed and the service they provided.

The Pennsylvania Hospital began its preparations before war was declared and after war came established Base Hospital No. 10 (United States Army). All equipment, supplies and material were furnished through private donations. Once war was declared the Hospital personnel were ready to move. Doctors, nurses and staff along with much of their equipment reached France on June 11, 1917 and were stationed at Le Treport. During Base Hospital No. 10’s service it primarily treated British Forces. Apart from general medical and surgical service the hospital also had a dental department, X-Ray and pathology departments. It even had its own band to give concerts for the staff and wounded. Base Hospital No. 10’s staff included 39 doctors, 125 nurses and 327 enlisted men. The Hospital was demobilized on April 22, 1919.

After America joined the war the University of Pennsylvania organized one base hospital, three ambulance units and several Red Cross units. Over $110,000.00 was raised from private donations to support these endeavors. What would become Base Hospital No. 20 (United States Army) began being organized in 1917 before America entered the war with the assistance of the American Red Cross. The hospital personnel, which included 22 medical officers, two dentists, one chaplain, 65 nurses and 153 enlisted men from Penn’s faculty, students, and alumni, reached France May 2, 1918. It was stationed in an old hotel with adjoining buildings in Chatel-Guyon, France. Some of those doctors are shown below. During its service in France the hospital cared for over 8,700 patients. Members of the hospital also adopted 15 French orphans.

The Episcopal Hospital of Philadelphia organized Base Hospital No. 34 (United States Army). It was supported by private donations of $65,000.00. Personnel and equipment reached France on December 26, 1917 and operations were set up in Nantes. It was demobilized and left France in April 1919.

Jefferson Medical College, founded in 1824, is located in Center City Philadelphia. Jefferson’s Base Hospital No. 38 (United States Army) was actually organized in May 1917. Private donations in the amount of $122,312.00 equipped the Hospital and provided the needed supplies. The Hospital unit included 6 ambulances which were donated by Philadelphia residents, the Philadelphia Teachers Association and the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company.

The Unit arrived in France in the first week of July 1918 and was stationed at Nantes with 35 doctors, 100 nurses and 200 enlisted men. Additionally a total of 1,462 graduates and 370 undergraduates of Jefferson Medical College served during the war in various branches of the military and Red Cross. During the hospital’s time in France it treated 9,000 patients. Five members of the hospital’s staff died in service.

The Methodist Episcopal Hospital, Naval Base Hospital No. 5 was organized, equipped and supplied by donations for the city’s Methodist Churches. It was staffed by 40 doctors and nurses and 90 enlisted personnel. It reached Brest, France on October 17, 1917. Once there it was given an abandoned nunnery (shown below) which had to be cleaned and refurbished to make suitable for hospital service. The hospital was originally expected to hold 250 beds but that estimate was quickly exceeded.

Presbyterian Hospital in conjunction with the American Red Cross organized Hospital Unit A in the spring of 1917. The hospital personnel included 12 Doctors, 21 nurses and 47 enlisted men. The Unit reached France on February 4, 1918. However, once in France due to the pressing needs of other, already established hospitals, the Unit was broken up and its members assigned to those hospitals.

I want to note in closing that the men and women of these and other hospital units often performed their duties under the most difficult and sometimes horrific conditions. At times they cared for the wounded and performed surgeries on the front lines with battle going on all around them including artillery bombardment and gas attacks. The bravery, dedication and sacrifice of these men and women of medicine should never be forgotten.

April 22, 2014 Tampico, Vera Cruz and The Philadelphia Connection

In April 1914 before there was any inkling of a war in Europe, before a shot was fired at Sarajevo, before European armies mobilized to face each other across fields of death, Americans fought and died in battle in Mexico.

A civil war had been raging in Mexico since 1911. As with all civil wars it was brutal, vicious and at times barbaric. Increasingly this war was encroaching across the Rio Grande and effecting American interests both here and in Mexico. On April 9, 1914 what would have been, in normal times, a minor incident quickly escalated into armed conflict between the United States and Mexico. It began in Tampico where those loyal to the usurper Victoriano Huerta were defending the area from the “Constitutionalists” led by Venustiano Carranza and Pancho Villa.

Nine unarmed American sailors on a small boat flying the American flag cast off from the U.S.S. Dolphin to go to Tampico to buy gasoline. The Americans had no way of knowing that the area they were heading for had been declared off limits to foreigners. Once they docked they were arrested. Neither side spoke the other’s language. The Americans failed to respond to the orders of the Mexican soldiers and were arrested and paraded through the streets to regimental headquarters.

Upon reaching the headquarters the local commander of the Mexican forces recognized the mistake and returned the Americans to their boat. The military governor of the area conveyed his regrets for the arrests to the commander of the American fleet Rear Admiral Henry Mayo. But Mayo was not easily appeased. He demanded an official apology and that a 21 gun salute be given to the American flag. This demand for a salute should not necessarily be considered outlandish. Just 6 days prior, on April 2nd, the American ships in the area had fired three (3) 21 gun salutes to the Mexican flag as part of the celebration of the defeat of the French intervention in Mexico in 1867.

Unfortunately, President Huerta refused this demand. President Wilson supported Admiral Mayo and relayed through diplomatic circles that the 21 gun salute must be given. A deadline of April 19th was set which passed without any salute.

On April 20th President Wilson addressed congress and asked for authorization to take military action against Huerta’s forces in Mexico. Specifically, Wilson said this incident and others committed by the forces of Huerta showed a disregard for the rights and dignity of the United States. Wilson was not a fan of Huerta and saw him as illegitimate. Wilson stated that the United States would not be entering hostilities against the Mexican people but only those supporting Huerta. And that force would only be used to ensure that General Huerta and his supporters recognize the rights and dignity of the United States in the future.

On April 21st, prior to receiving congressional approval, President Wilson ordered the occupation of Vera Cruz, a port city 240 miles southeast of Tampico. This was done to stop the delivery of arms from the German ship S.S. Ypiranga to President Huerta’s army. Eight hundred American sailors and marines entered the city. Over the course of the next 2 days reinforcements arrived. By April 24th all of Vera Cruz was under American control. When the fighting finally ended 19 Americans and 190 Mexicans were dead. American forces would remain in Vera Cruz for 7 months, leaving in November 1914. The occupation helped in Huerta’s downfall, something in which President Wilson took a certain satisfaction. However, the United States never received the 21 gun salute to her flag.

Philadelphians followed the news from Mexico as closely as other Americans. But when it was learned that two of their own were among the casualties, the sorrow and anger in the city was palatable. Seaman George Poinsett (5321 North 12th Street) and Seaman Charles Smith (2168 East Sargent Street) were Philadelphia’s dead. It was reported that Poinsett was the first American killed as he carried the American Flag in front of advancing troops. Smith lost his life the next day while trying to retrieve an American Flag that had been dropped in the fighting.

On May 13, 1914, Philadelphia had what can best be described as a state funeral for the dead sailors. The city’s government offices, businesses and schools closed and an estimated 500,000 people lined the streets to view the funeral procession of the caissons carrying the bodies. The caskets were taken to Independence Hall where they lay in state as thousands of mourners paid their respects. The local boy scouts raise funds for a statute depicting Smith to be raised in McPherson Square in Kensington, where it stands today. A memorial to Poinsett stands at Broad Street and Tabor Road.

April 14, 2014 April in Philadelphia in 1914

In the months leading up to the First World War, Philadelphians like most Americans were generally uninterested in European events. Of course they read of the weddings, engagements, illnesses and scandals of the European nobility. Fashion trends from Paris were followed and the great artists, like Anna Pavlova and Enrico Caruso, were feted and applauded when they performed in the city. But the political machinations of Europe were something the average Philadelphian spent little time reflecting on.

For Philadelphians, April brought spring. And spring brought sports, especially baseball. The World Champion Athletics were back on the field coming off their victory over the New York Giants in just 5 games. And the Phillies were back. After finishing 2nd in the National League fans of the team were hoping for that elusive championship so long overdue. Some were even quietly praying for an all Philadelphia World Series. But that was not to be. Although the Athletics would again win the American League Pennant, the Phillies would finish a disappointing 6th place in 1914.

Philadelphia sports fans were ravenous when it came to baseball. They followed local college teams like Penn, Villanova and St. Joseph’s and high school teams such as Central, West Philadelphia, South Philadelphia and Roman Catholic. There were also industrial leagues and amateur clubs. Baldwin Locomotive Company, Cramps Shipyard and even Lubin Movie Studio had organized clubs. And in the city there were at least 50 full time amateur clubs playing weekly.

But baseball wasn’t by any means the only sport followed in the city. Fans also flocked to college and high school track and field meets. As well as soccer, golf, cricket, squash and shooting. On the court “Big Bill” Tilden of Germantown was taking the tennis world by storm. And the rowing meets or regattas on the Schuylkill River were a popular attraction. These events were hosted by “The Schuylkill Navy” and included the Vesper, Malta, University and Bachelors Barge Club. All of which are still on the river today.

Philadelphia also had dozens of boxing clubs scattered throughout the city. Back then the city was considered a boxing capital producing champions in every class. One of the most followed boxers was Barney Lebrowitz who fought as “Battling Levinsky.” Levinsky, like most Philly boxers, grew up in the crowded inter city streets where using one’s fists was a necessity. He would become World Light Heavyweight Champion in 1916.

So even though April arrived in Philadelphia cold and wet in 1914 it brought with it the thoughts of sunny spring and summer days at the ball game, afternoons along the Schuylkill, and early evening strolls in one of the many city parks.

April 7, 2014 The First World War Years In Philadelphia

This blog is dedicated to the city of Philadelphia and its people during the years encompassing the First World War. My intent will be to provide the reader with a sense of what life was like in the city during those days and tell the stories of some of the men and women of Philadelphia and the surrounding area who served, fought, sacrificed and died in the Great War.

In 1914 Philadelphia was the 3rd largest city in the United States with a population of over 1.5 million people. In contrast to the image of outsiders who saw it as a conservative and sleepy town it was a bustling, active, dynamic and energetic city. It was a major manufacturing center and nicknamed “The Workshop of the World.” Industries, both large and small, dotted the city’s landscape and shared neighborhoods with the miles of two and three story row homes that Philadelphia was famous for. Along with its hundreds of manufacturing and textile mills the city’s seaport along the Delaware River was home to six ship building yards including the United States Navy Yard.

When America entered the war against Germany in April 1917, Philadelphia mobilized like few other American cities. Almost overnight, Philadelphia’s manufacturing and textile companies converted to full war-time production. Private and city-sponsored organizations previously created to send relief to the people of war-torn Europe now marshaled their money, time, and efforts to support America’s war and our boys.

The shipyards on the Delaware River waterfront would produce hundreds of ships for the military including battleships, destroyers, submarine chasers, and troop transports. Hog Island Shipyard was built in a little more than six months and became a city within a city. At its completion, it was the largest shipbuilding facility in the world. Hog Island, along with the already established private shipyards on the Delaware River and the United States Navy Yard at League Island, made Philadelphia one of the greatest centers of ship construction in the world.

The “Great War” years would forever change the city’s landscape and its people. Philadelphia would experience sweeping change, and the people of what its founder, William Penn, called his “greene country towne” would come together as never before to support the war effort at home and their boys over there. And they did it the Philadelphia way, with the values that Philadelphians from all the social, economic and ethnic groups agreed on – hard work, perseverance, stubbornness and a dogged determination to get the job done and win the war.

I hope you will visit my blog each week and that you will find the stories interesting and enlightening. If you would like to read a daily entry about events please visit the Life in the City section of the web site. And if you have a story you would like to share about a family member or just something about the city or its people during that time, please email me at PhillyWWIyears@gmail.com.

Finally, let me say that this is my first venture into the world of blogging so it will be a work in progress and a learning experience. I do hope you will excuse the occasional mistake and miscue while I learn the craft.